The son of poor villagers, a spy boss, and now the man behind dizzying attempts to reform Africa’s fastest-growing economy and heal wounds with Ethiopia’s neighbours, Abiy Ahmed has seen an unpredictable and peril-strewn rise to fame.

Another chapter was added to his remarkable tale on Friday when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Abiy was honoured “for his efforts to achieve peace and international cooperation, and in particular for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea,” the jury said.

Since becoming Ethiopian prime minister in April 2018, the 43-year-old has aggressively pursued policies that have the potential to upend his country’s society and reshape dynamics beyond its borders.

Within just six months of his swearing-in, Abiy made peace with bitter foe Eritrea, released dissidents from jail, apologised for state brutality, and welcomed home exiled armed groups branded “terrorists” by his predecessors.

More recently he has turned to fleshing out his vision for the economy while laying the groundwork for elections currently scheduled to take place next May.

But analysts fret that his policies are, simultaneously, too much too fast for the political old guard, and too little too late for the country’s angry youth, whose protests swept him to power.

Despite the challenges, Abiy’s allies predict his deep well of personal ambition will prompt him to keep swinging big.

Tareq Sabt, a businessman and friend of Abiy’s, says one of the first things that struck him when they met was the prime minister’s drive: “I always said to friends, when this guy comes to power, you’ll see a lot of change in Ethiopia.”

Born in the western town of Beshasha to a Muslim father and Christian mother, Abiy “grew up sleeping on the floor” in a house that lacked electricity and running water.

“We used to fetch water from the river,” he said in a wide-ranging radio interview with Sheger FM last month, adding that he didn’t even see electricity or an asphalt road until the seventh grade.

Yet Abiy progressed quickly through the power structures created by the ruling coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), after it took power from the Derg military junta in 1991.

Fascinated with technology, he joined the military as a radio operator while still a teenager.

He rose to lieutenant-colonel before entering government, first as a securocrat—he was the founding head of Ethiopia’s cyber-spying outfit, the Information Network Security Agency.

He then became a minister in the capital Addis Ababa, and a party official in his home region of Oromia.

The circumstances that led to Abiy’s ascent to high office can be traced to late 2015.

A government plan to expand the capital’s administrative boundaries into the surrounding Oromia region was seen as a land grab sparking protests led by the Oromo, Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group, and the Amhara people.

States of emergency and mass arrests—typical EPRDF tactics—worked to quell the protests but failed to address the underlying grievances.

When then-prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn abruptly resigned, many feared a power-struggle within the EPRDF, or even an unravelling of the coalition that would leave a dangerous vacuum.

Instead, the coalition’s member parties chose Abiy to become the first Oromo prime minister.

“He’s the only one that could have saved the EPRDF,” said Mohammed Ademo, a journalist who accompanied Abiy on his first visit to the large Ethiopian diaspora community in the United States last year.

“My feeling is that he’s prepared for this moment all his life.”

As prime minister, Abiy has sought to shape events across the Horn of Africa, fuelling criticism that he is taking on too much at once.

Beyond the rapprochement with Eritrea, for which he was cited for the Nobel, he has played a leading role in mediating Sudan’s political crisis and has also tried to revive South Sudan’s uncertain peace deal.

Yet whether any of these initiatives will ultimately succeed is an open question.

Even the Eritrea deal, which many see as Abiy’s signature achievement to date, has been undermined by a lack of tangible progress on critical issues like border demarcation.

“Abiy has had real foreign policy successes, but there has been some misguided optimism from abroad that he can transform the Horn of Africa,” said James Barnett, an analyst specialising in East Africa at the American Enterprise Institute.

“The Horn is volatile. I’m sceptical that one leader can undo decades of competition and mistrust.”

Hurdles

The immediate demands of Ethiopian politics may leave Abiy with no choice but to shift his focus inward in the months to come.

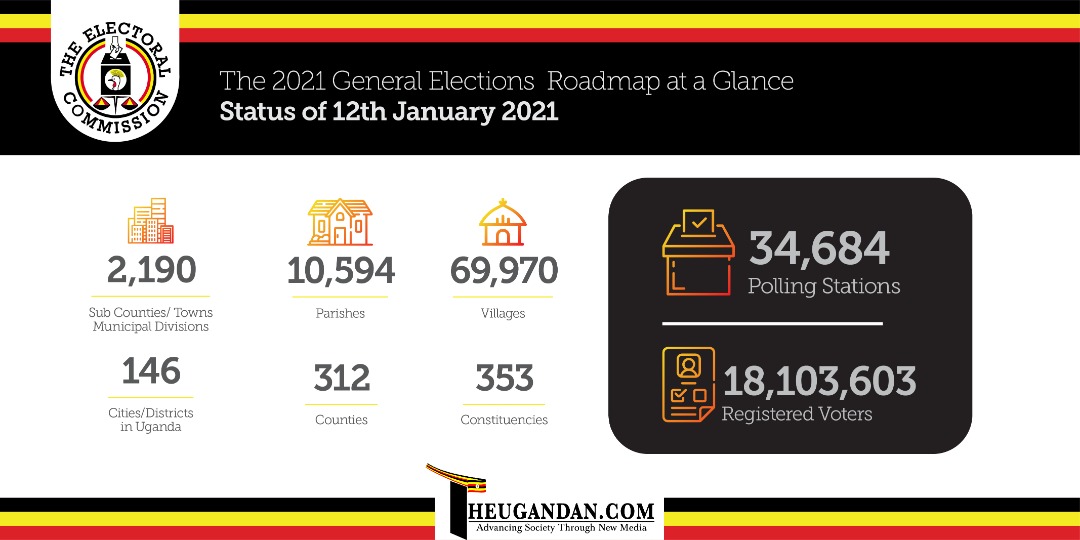

Holding credible elections by next May, the current timeline, is a daunting task, yet Abiy is keen on scoring the kind of victory that would give him a mandate with the general public.

First, he must contend with Ethiopia’s formidable security challenges.

Ethnic violence has been on the rise in recent years, causing Ethiopia to record more internally displaced people last year than any other country.

And last June, Abiy faced the greatest threat yet to his hold on power when gunmen assassinated high-ranking officials including a prominent regional president and the army chief.

Abiy seems well aware of the danger he faces, and from time to time makes public reference to attempts on his own life, including a grenade attack at a rally just two months after he took his post.

For now, as he noted in the Sheger FM interview, he remains in control.

“There were many attempts so far, but death didn’t want to come to me,” he said. “Death shied away from me.”

By AFP