By Don Wanyama

Ever since the Electoral Commission chairman, Justice Simon Byabakama, announced a revised roadmap to the 2021 elections on June 16th and qualified that process with guidelines that bar large gatherings, especially processions and rallies, the country has been plunged into a raging debate on what this exactly means for our democratic processes.

A dominant argument, especially from the Opposition and some NRM MPs, is that an election that is run mainly on electronic (digital) platforms is undemocratic, has a limited reach to voters and its results will not reflect the people’s will. This group is advancing the view that a state of emergency be declared, the life of Parliament is extended and elections deferred for at least six months.

A case against extension

That argument would only be practical if indeed we were certain that at the end of the six-month extension, an answer would have been found to the question that has brought us into the current situation. A scientific election is being mulled because the world is battling a new, complex pandemic.

By now, all readers must be aware of the damage and discomfort this Covid-19 pandemic has occasioned globally. Over half a million lives have been lost and more still at risk of being lost, especially with new waves emerging in countries like China, which many thought had successfully battled this disease.

We can only say the pandemic is under control or has been defeated once a cure or vaccine is found and made available on the world market.

From the look of things, we are still far away from this breakthrough, considering that on Saturday July 4th, the World Health Organisation, on the advice of the Solidarity Trial International Steering Committee (a body that WHO established to find effective treatment for COVID-19 patients) discontinued the trial of the drugs; hydroxychloroquine and lopinar; which were being piloted as trial drugs.

Seeing that the process of cobbling an effective cure is a long-drawn one, there are no guarantees that in six months, we shall have a cure. In fact, for Africa, scientists still predict that we are yet to hit our peak, considering that the pandemic arrived in the continent much later. What then happens at the end of an extension? Do we again extend the already extended government? We run the risk of being caught up in a circus and a constitutional quagmire if we go this way.

In that case, the most logical thing to do is hold an election even in these circumstances, manage the key dynamics such that risk of exposure/transmission of COVID-19 is greatly minimised and yet still ensure the results of the election reflect the peoples will. This is what the Electoral Commission is doing. It is just not elections, many facets of life are taking very new shapes in what has been christened the “new normal”.

Radio & phone are key

With the idea of large gatherings of voters off the table, the big question now is whether the media, which becomes the key campaign platform suffices, both in terms of reach and availability. Let us look at some statistics derived from UBOS, the Electoral Commission and Uganda Communications Commission (in the table below).

In arguing against electronic/media campaigns, the proponents have presented a picture of a media having limited reach, insisting that rallies and its accompanying fanfare is the answer. The statistics, however, paint a less worrying picture. About 60% of all households in Uganda own a radio set.

Whereas the 40% gap would be a worry, we need to know that many people today actually listen to radio on their mobile phone handsets. It is not unusual to pass by a couple in a garden or builders at a site, listening to their favourite radio station on a mobile phone usually placed on loudspeaker.

That is why the mobile phone ownership and FM sound broadcast (or rather radio frequency coverage) become key here. With over 27 million phone subscribers, it means nearly all of Uganda’s adult population has a mobile phone or can access one.

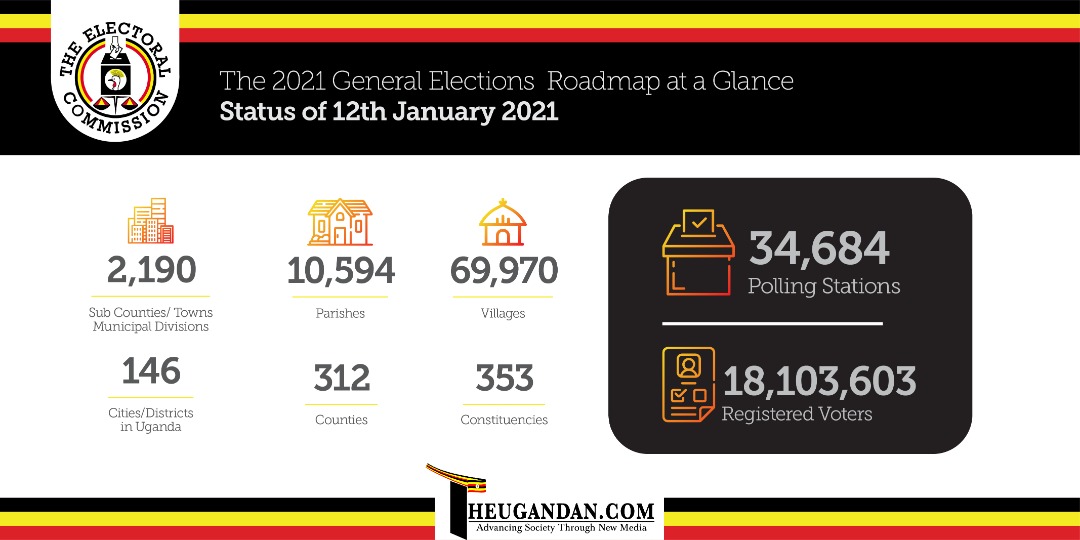

Remember we have just over 17 million voters registered for the 2021 elections, and yet for the past five elections, none has registered over 75% voter turn up. The highest voter turn-out (in percentages) so far was 1996 where 6,163,678 voters turned up or 72.3% of registered voters. The others have been 2001 (7.5m voters or 70.3%), 2006 (7.2m voters or 69.1%), 2011 (8.2m voters or 59.2%) and 2016 (10.3m voters or 67.6%)

Therefore, even if it is ideal to get an extra 3 million radio sets (like the government is planning, so that each and every household has one), we cannot expect a 100 voter turn-out. Whereas TVs and the Internet (digital/social media) are not as penetrative as radio/phones, the demographics show that their consumers are key decision makers or influence opinion and therefore a critical audience for candidates. The younger people, especially, who will form the bulk of voters in 2021 have access to the Internet.

Fair playground

The resultant discussion therefore should not be whether voting Ugandans can be accessed through the media rather how to structure and guide the media to ensure a level playground for different candidates in different clusters. This is where the MPs and civil society should channel their energies—and therefore would have demanded the Executive and regulators like the Uganda Communications Commission and the EC to give them available options.

For example, in the case of parliamentary candidates, the key radios in the region would be asked to host debates where all candidates for a specific seat appear on a single show and make their case to the listeners. A national presidential debate on key national media would be ideal too.

The painful reality though is that just like a candidate with more resources and perhaps better organisation would attract a larger crowd in case rallies and processions were allowed, those with better resources and resonating messages will naturally get more airtime in the media. It’s the case everywhere even in places like the US where a candidate who raises most money runs most advertising and influences opinion. Besides these media platforms, candidates can use paraphernalia like flyers, posters, T-shirts, to popularise themselves and their messages among the voters.

Will human-to-human contact be totally eliminated in these elections? I don’t think so. The Justice Minister has already tabled regulations to guide political parties especially as they prepare for primaries. Ultimately, I believe the Electoral Commission will have to allow, for example, presidential candidates to host key events (manifesto launch, unveiling taskforces) that can accommodate say 100 delegates, with SOPs observed in a spacious venue.

The bottom line is that messages can still get to voters even if done “scientifically”. It might be a campaign devoid of music, dance and drink but it would be an election of issues and whose outcome will still reflect the voters’ will.

The writer is the Senior Press Secretary to His Excellency the President

Twitter: @nyamadon