Finally, Jennifer Musisi has resigned as executive director of KCCA. This was inevitable. However, her resignation points to a deeper malady that our nation faces: the gulf between our theoretical ambitions and the pettiness of our politics. Musisi has fallen because she aspired to do great things for a city the majority of whose residents are driven by petty politics.

To understand Musisi’s fall, one has to first take a look at results of presidential and parliamentary elections for Kampala district for 2011 and 2016. This is because Musisi was appointed with fanfare after the 2011 elections. The 2016 election was the one to determine whether her reforms had generated political capital for Museveni and his NRM or had decimated it in the city.

In 2011, Museveni got 226,000 votes against Besigye’s 229,000, a difference of a little more than 3,000 votes. In the same elections, NRM won three parliamentary seats in Kampala against the combined opposition which won six seats. In fact, NRM candidates had been competitive in Kampala, only losing narrowly.

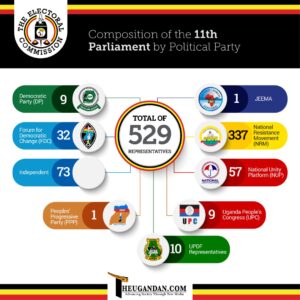

In 2016, Museveni and the NRM faced a total rout. Museveni’s votes fell by 30% to 157,000 while Besigye rose by more than 50% to 335,000. In short Besigye, who had a small lead of 3,000 votes now garnered a staggering lead of 180,000 votes, more than double the total votes Museveni got in Kampala. Not a single candidate on the NRM ticket in Kampala was elected to parliament.

There is a correlation between the reforms by Musisi and the near collapse of the NRM and Museveni in Kampala. It was clear after 2016 elections Museveni would have to stop any reform Musisi was promoting. The democratic forces of this city may want a clean and beautiful city but they are not willing to accept the price it takes to achieve that goal.

Anyone who followed the conversations inside NRM after the 2016 elections would wonder why Museveni did not fire Musisi to appease his supporters in Kampala. Former NRM MP, Mohamed Nsereko, now an independent, gave me a long explanation on why Musisi was a disaster for NRM. In trying to make Kampala great, she alienated the thieves inside City Hall whose corruption lubricates NRM’s electoral machine.

In her resignation, Musisi listed all her achievements which I find commendable. But the issue for politics in Kampala, and for Uganda, is not the great works that will develop this country and make it great or make our city beautiful. The issue is that the democratic forces who have votes have interests at odds with such a grand vision.

We forget that Europe did not develop because the interests of its masses of ordinary citizens were listened to. Indeed, universal adult suffrage came after these countries had transitioned from poor agrarian societies into modern industrial nations. What transformed Europe was the capture of power by the bourgeoisie and the use of that power to promote their interests, often by suppressing popular classes.

When Musisi was appointed, I thought our bourgeoisie had come of age. I argued then that because they have invested the money they have stolen from government or earned genuinely in their business in hotels and other things around Kampala, now we have developed a constituency inside power with a vested interest in an organized city. I thought these people would use their influence to push through the reform of Kampala.

Indeed, the original KCCA act had removed elections from the city. In fact, the original bill envisaged a technocrat-managed city. Museveni forced an amendment so that Kampala retains some democratic content. Hence the retention of elections and the detriment this has brought to our city.

Hence the resignation of Musisi only proves the triumph of populist politics over progressive policy and management of Kampala. The votes are with vendors, hawkers, Boda Boda riders and such other popular forces. To expect a first class city when the decisions about its development are heavily influenced by such social groups is to expect cardinals to spread Islam.

This argument also works for Uganda’s pretentious efforts to develop. This country’s politics is dominated by social groups without a vested interest in social transformation. The elites in politics are professionals looking for salaried employment. The voters are predominantly peasants, vendors and hawkers. How can such a coalition produce anything other than patronage politics?

It really doesn’t matter whether Museveni or Besigye or Bobi Wine is in power. The forces behind each of these individuals are the same – narrow minded with very parochial interests. That is the real crisis of Africa. One day, I will explain why post genocide Rwanda is different from the rest of Africa, and why in spite of the social base of its ruling elites being similar to ours, it pursues progressive politics aimed at social transformation.